Medical errors are linked to 440,000 deaths each year. New Ratings can help you find a safe hospital.

Published: March 2014

Twelve years ago, John James’ 19-year-old son died after cardiologists at two Texas hospitals made a series of mistakes. James says they failed to properly diagnose and treat the cause of an abnormal heartbeat. At the time he was the chief toxicologist for NASA in Houston, responsible for overseeing the air astronauts breathe in space. Now retired, he has responded to the tragedy by dedicating his life—and his son’s memory—to improving hospital safety.

He founded Patient Safety America, an organization that educates people about risks they may face in hospitals. He became active in Consumer Reports’ own Safe Patient Project, which works with people across the country who have been harmed by medical care. And last year he authored a comprehensive analysis on the number of people who die at least in part because of medical errors in hospitals.

His conclusion—published in the Journal of Patient Safety, a peer-reviewed medical journal—was sobering. He estimated that 440,000 people each year die after suffering a medical error in the hospital. Some patients, for example, might have gotten the wrong drugs or developed infections because doctors or nurses failed to wash their hands. Others may have failed to get needed tests or treatments.

“Four-hundred-forty-thousand is a frightening figure,” James says. It’s more than 1,000 deaths per day, for example, or more than half of the deaths that occur in U.S. hospitals each year. “And it makes patient harm in hospitals the nation’s third leading cause of death, trailing only heart disease and cancer,” James says.

Too many deaths

James, like other researchers who have studied hospital safety, is quick to emphasize that his analysis is inexact. Establishing firm numbers is hard, in part because much of what happens in hospitals goes unrecorded, and because untangling how much any hospital death stems from an underlying health problem and how much stems from medical error is messy, complicated, and sometimes controversial.

John James, Ph.D., authored a major study on hospital safety after his son’s death

But his figures are in line with other research. Fifteen years ago the Institute of Medicine stated that up to 98,000 hospital patients per year die from medical errors. Almost four years ago the Department of Health and Human Services estimated that 180,000 people each year die in part because of their hospital care—but that was limited to Medicare patients. James’ analysis—which was based on the results of four key hospital safety studies, all published between 2008 and 2011—pushed further by, for example, estimating the number of deaths caused by errors that go unrecorded or that stem from missed diagnoses.

“The truth is that whether it’s 100,000 or 200,000 or 400,000 deaths a year is almost immaterial,” says James. “What matters is that too many people are dying in hospitals because of medical mistakes, not enough is being done to stop it, and patients need more information.”

Our hospital safety score helps fill that gap. It includes information for a record 2,591 hospitals in all 50 states plus the District of Columbia, combining five measures of patient safety into a 1 to 100 score. And our score includes new information on hospital mortality rates. As in James’ analysis, the results are sobering. (See our full hospital Ratings, with some information on more then 4,000 hospitals.)

What we found

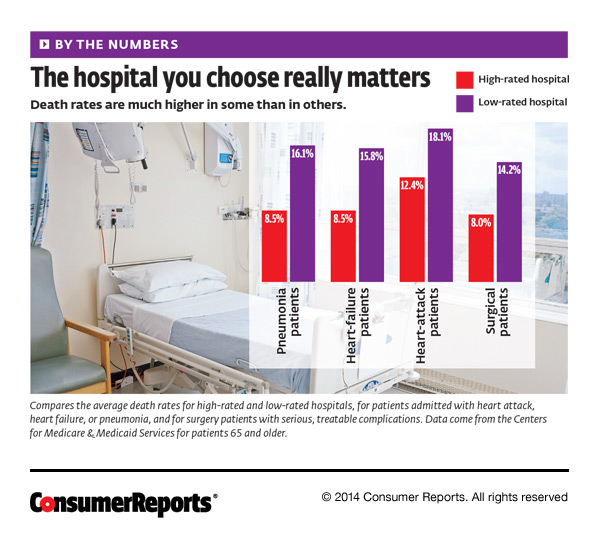

Our analysis uses two measures of hospital mortality, both using information from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services—the most recent, reliable, and comprehensive data publicly available—on patients 65 and older. The first focuses on hospital patients admitted with medical conditions, such as heart problems; the second, on surgery patients.

Medical patients

This is based on the chance that a patient who has had a heart attack or been diagnosed with heart failure or pneumonia will die within 30 days of entering the hospital. Only 35 hospitals nationwide earned a top rating in the measure. By comparison, 66 hospitals got our lowest rating.

“The differences between high-scoring hospitals and low-scoring ones can be a matter of life and death,” says John Santa, M.D., medical director of Consumer Reports Health. For example, pneumonia patients at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, which earned a top rating in this measure, had a 7 percent chance of dying within 30 days. That compares with a 22 percent chance of death for similar patients at Delano Regional Medical Center, 2 hours north in Delano, Calif. Overall, pneumonia patients in top-scoring hospitals are at least 40 percent less likely to die within 30 days of admission than similar patients in low-scoring hospitals.

Surgical patients

This looks at surgery patients who had serious but treatable complications—such as blood clots in the legs or lungs, or cardiac arrest—and died in the hospital. More hospitals did well in this measure, with 173 earning a top rating. By comparison, 228 hospitals got our lowest rating. And again, the differences between high- and low-scoring hospitals are dramatic: For every 1,000 patients who develop serious complications in a top hospital, 87 or fewer die; in a low-rated hospital, more than 132 die. Patients in top-rated hospitals are at least 34 percent less likely to die than similar patients in low-rated hospitals.

High- and low-scoring hospitals

Seven hospitals in the country earned a top Rating in both medical mortality and surgical mortality (listed alphabetically):

- NYU Langone Medical Center, New York City

- Olympia Medical Center, Los Angeles

- Presence Saint Joseph Hospital, Chicago

- Providence Hospital, Southfield, Mich.

- South Pointe Hospital, Warrensville Heights, Ohio

- St. Alexius Medical Center, Hoffman Estates, Ill.

- UPMC McKeesport, McKesport, Penn.

Three hospitals got our lowest score in both measures (listed alphabetically):

- Conway Regional Medical Center, Conway, Ark.

- Highland Hospital of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y.

- Lake Cumberland Regional Hospital, Somerset, Ky.

Note that hospitals may have done better or worse on other performance measures. For details on, click on each hospital’s name, above. Read more about how we rate hospitals.

Staying alive

Why do some hospitals do a better job than others at keeping patients alive? “Likely because they do a lot of things—some little, some big—well,” Santa says. “That includes everything from making sure staff communicates clearly with patients about medications, which can help prevent drug errors, to doing all they can to prevent hospital-acquired infections.”

That’s what they’ve done at Sanford Medical Center, at the University of South Dakota in Sioux Falls. It earned the highest safety score of any teaching hospital in the country and also got a top rating in avoiding death in surgical patients. The hospital instituted strict protocols for hand washing, says Mike Wilde, M.D., chief medical officer at Sanford, as well as for inserting and removing urinary catheters and central-line catheters, which provide drugs, fluids, and nutrition to patients. Those are two of the most common and deadly causes of infections in hospitals.

Accountability is also key. “It’s easy to blame a provider, but a lot of times it can be the systems in place,” Wilde says. So the staff now examines whether errors stem from a poorly functioning device or a failure to follow a safety protocol.

When a patient does die from a preventable error, there should be a thorough examination of why and steps taken to prevent similar errors in the future. “I want to know if someone dies on my watch or after they have left my watch, why they died, and how the death might have been prevented,” says Don Goldmann, M.D., chief medical and scientific officer of the nonprofit Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

That kind of soul searching can yield better care. In 2006, the University of Pennsylvania Health System established a Mortality Review Committee. One program they came up with focused on detecting sepsis, a bloodstream infection, and starting timely and appropriate antibiotic treatment. Survival rates of hospital patients with severe sepsis rose from 40 percent to 56 percent. And survival rates from septic shock, which occurs when the infection causes blood pressure to plummet, rose from 42 percent to 54 percent.

What you can do

Doctor Discussing Medicine in His Clinic With a Patient

“Informed, active patients and family members are the best defense against hospital errors,” James says. Lisa McGiffert, head of the Consumer Reports Safe Patient Project, agrees. Here are three of the most important steps she says patients should take to stay safe in the hospital:

- Have a friend or family member with you to be your advocate when you are unable to speak up for yourself.

- Before a planned hospitalization, do your homework. Learn as much as you can about what to expect while at the hospital, and ask about your treatments, especially medications or tests.

- If something goes wrong, keep a journal documenting what is happening.

To learn more, watch the video on patient safety produced by the Safe Patient Project, with advice from patients harmed in the hospital. And read our Hospital Survival Guide for more tips.

Editor’s Note:This article also appeared in the May 2014 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.